Industries have very predictable life cycles.

It starts with the “Pioneer Stage”: Dozens (if not hundreds) of manufacturers all try and promote different designs of a new product category.

Then the “Adoption Stage”: The market starts selecting the dominant designs and features and there is a refinement of those designs and features.

Next, the “Consolidation Stage”: Cost becomes important for mass-market adoption, but only 2-3 dominant firms emerge with the scale necessary to tackle it. There is a die-off of most manufacturers and remaining firms survive by providing products designed for very niche applications.

Finally, the “Disruption Stage”: The 2-3 dominant firms enter into a bucolic stupor: focusing on incremental innovation only and eventually becoming incredibly locked into their business model. A “disruptor” then enters the scene with a new business model causing the 2-3 dominant firms to lose their shit.1

Let’s look at how this played out in the car industry.

Pioneer Stage. Ever hear of Pope Manufacturing Company? How about Hupp Motor Car Company? Duesenberg? Likely you haven’t but these companies were pioneers in the car industry. And there were dozens like them building what we would consider crazy designs and powertrains.

Adoption Stage. The configuration layout of modern cars (steering wheel, gas pedal, brake pedal, etc.) was first truly locked in by Cadillac; the market also decided against electric and steam powered cars (good-bye Baker Motor Vehicle Company) and adopted the internal combustion engine as the dominant powertrain set up.

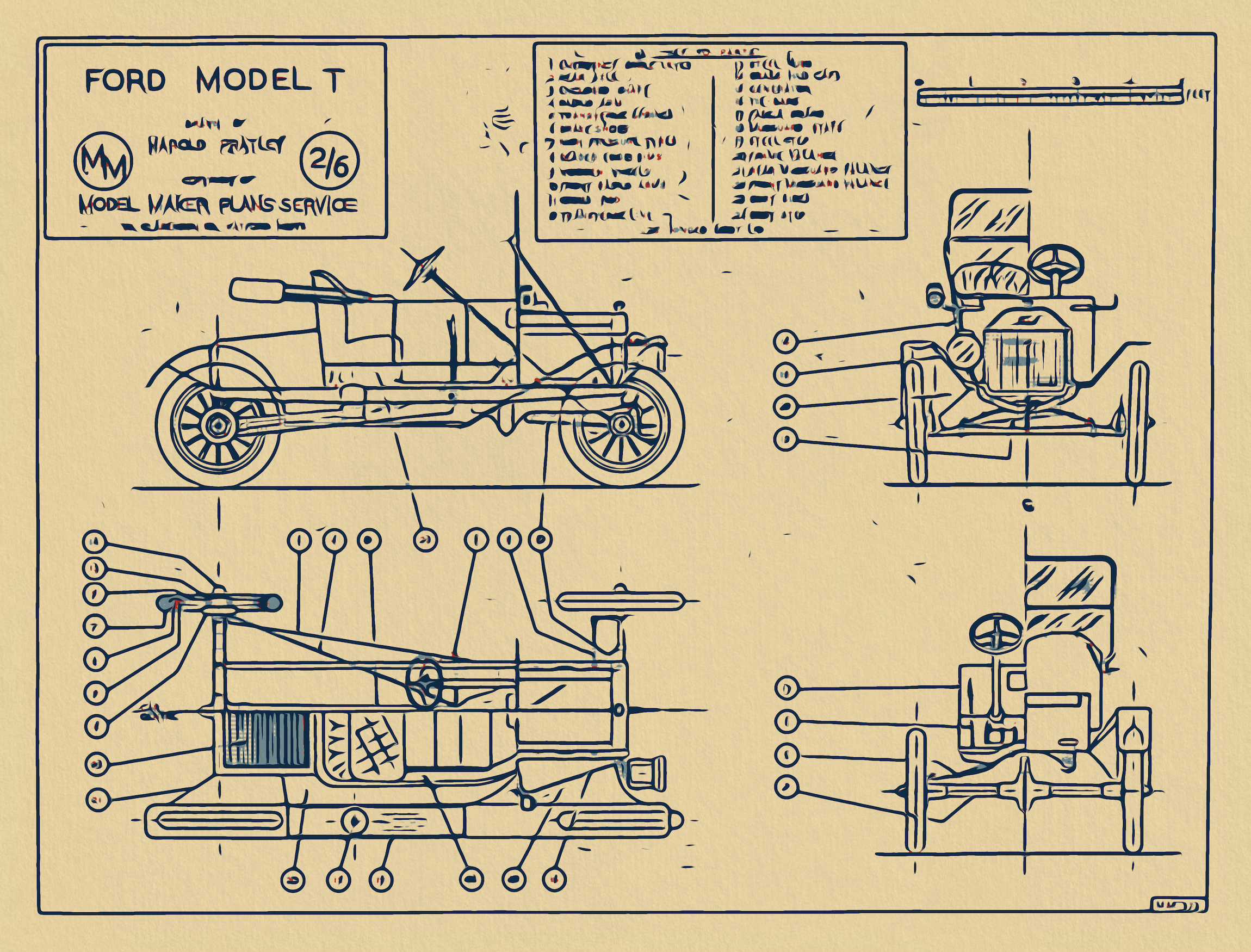

Consolidation Stage. Then enter Henry Ford and the Model T: mass production techniques, which results in a massive decrease in cost, which in turn results in mass-market adoption, etc. The initial pioneer companies start dying off leaving General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler as the dominant firms standing.

Disrupter Stage. Those dominant firms, GM, Ford, and Chrysler, had entered into a bucolic stupor extending through the 1970s, at which point they were quasi-disrupted by Japanese and German car firms, but they managed to stay the course (i.e., continue their bucolic stupor) because of import restrictions and a market preference for large truck-like things called SUVs. But then enter Tesla with a truly new business model and product. Will the disrupter prevail? As of now, it looks like yes. GM and Ford are tripping over themselves with electric car design. Chrysler isn’t even trying.

Well, where are we in the “industry life cycle” with drone industry?

We believe that we’re in the process of migrating from the Pioneer Stage to the Adoption Stage. It’s well known now what collection of sensors and features commercial drone operators want so now its just a matter of refining those.

That means the Consolidation Stage is on the horizon. And this then is the ultimate question: Who will produce the Model T of drones?

As we’ve talked about in previous articles here, this is why Cost-Per-(Flight)-Minute (CPM) is such a crucial metric. It tells you what drones are the lowest cost to purchase and operate. The drone manufacturer who dominants in the Consolidation Stage will almost certainly have the lowest CPM drones – and be the Model T of drones.

We could call it the “Modovolo T.”

You can pre-order your Modovolo Lift here. Only 200 pre-orders available.

- You may have noticed that this is the inverse of the technology adoption cycle popularized by Geoffrey Moore in his book, “Crossing the Chasm,” which focuses on how the end-customer adopts technology. The “industry life cycle” looks at how the manufacturers react to that technology adoption cycle. ↩︎

Very interesting points you have remarked, thank you for putting up.Money from blog